I remember trying to decide which ICS placement to choose and thinking ‘El Salvador is meant to be one of the worst countries in the world to be a woman, that’s got to be the one for me!’. As a feminist activist, I was excited to come to a country with little gender equality to offer my help, little did I know then that the most helpful thing I can do here is actually to learn.

Let’s talk through the recent history of this country and its attitude towards women. This is a country that saw years of disastrous massacres against the rural, poverty-stricken communities until the civil war ended just 24 years ago. When I walk around the town, I am aware that anyone here above the age of 30 almost definitely experienced the unjust and brutal assassinations of loved ones. The amount of trauma this community has suffered is like nothing I have come across before, and for the women it is even more complex than for the men.

Unfortunately, with many wars of this sort, a popular scare tactic used to gain control is the sexual abuse of women. The stories from the women of Arcatao make it clear that both the torture and assassination of women was a different story to that of men. Women’s bodies were sexually violated, penetrated and their sex organs mutilated. Their bodies became overlooked victims of the war just like the environmental terrain of the conflict left behind. As Gita Sahgal of Amnesty International stated, the psychology behind this military violence comes back to the idea that women are seen as the creators of life. When a group of people want to undertake a social cleansing it does so by attacking the roots and impregnating the womb of the enemy. This is the same reason so many babies and children were killed; people who were not necessarily rebelling against the government were carelessly murdered because they symbolised new life, life that could one day become the opposition.

Sadly, despite the peace accords, the war on women here in El Salvador has still not ended. The Small Arms Survey states that El Salvador has the highest rates of femicide in the world. Femicide is a widely unrecognised term meaning the brutal and deliberate murder of women purely because of their gender. It has high rates throughout Latin America due to the drug trafficking and therefore the presence of gang culture. The majority of the perpetuators are partners or family members, yet less than 3% of femicides cases are taken to court. The same applies to other forms of violence against women, such as domestic, sexual, and financial. "Survivors face emotional torment, psychological damage, physical injuries, disease, social ostracism and many other consequences that can devastate their lives," says Amnesty. When victims don’t see any hope or benefit in denouncing a violation, the perpetrators remain unpunished and free to strike again. So what can be done to stop the figures from rising further?

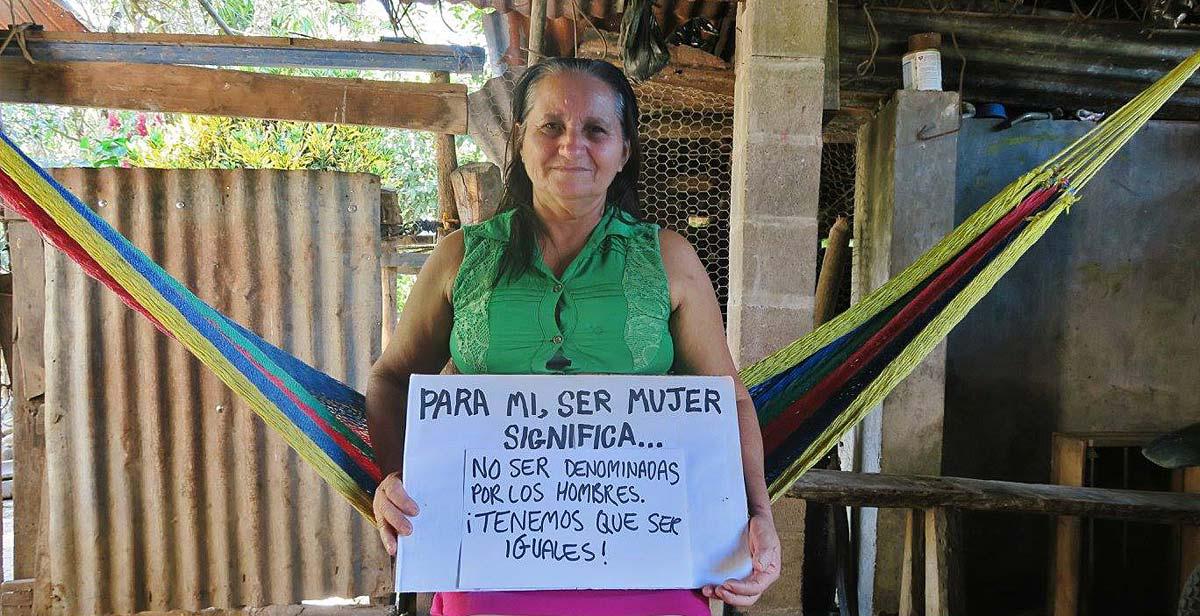

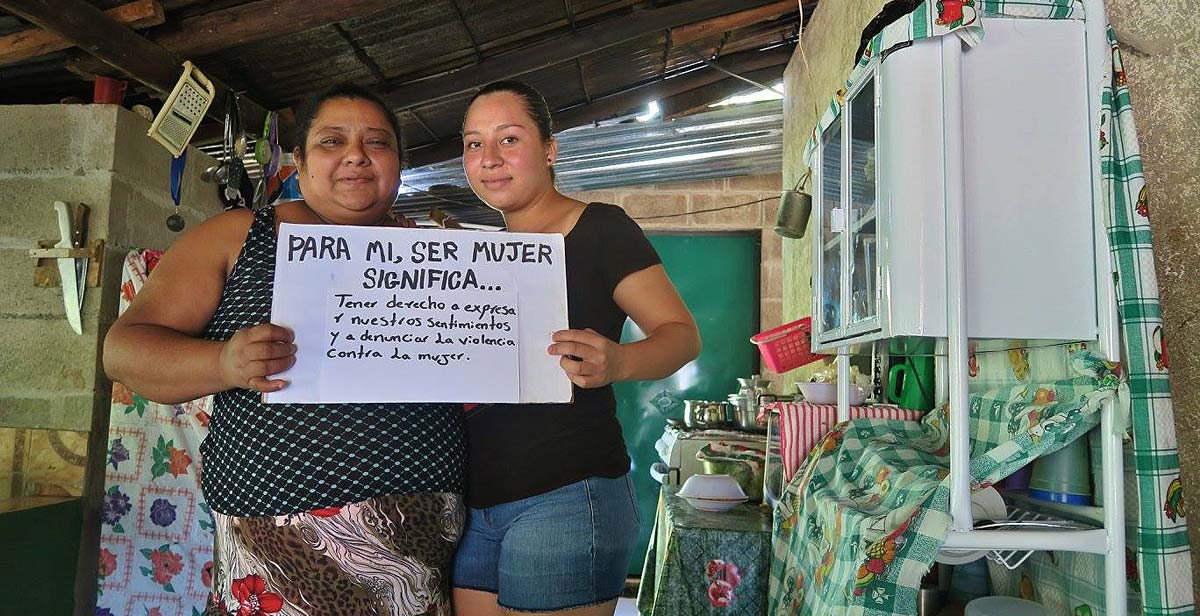

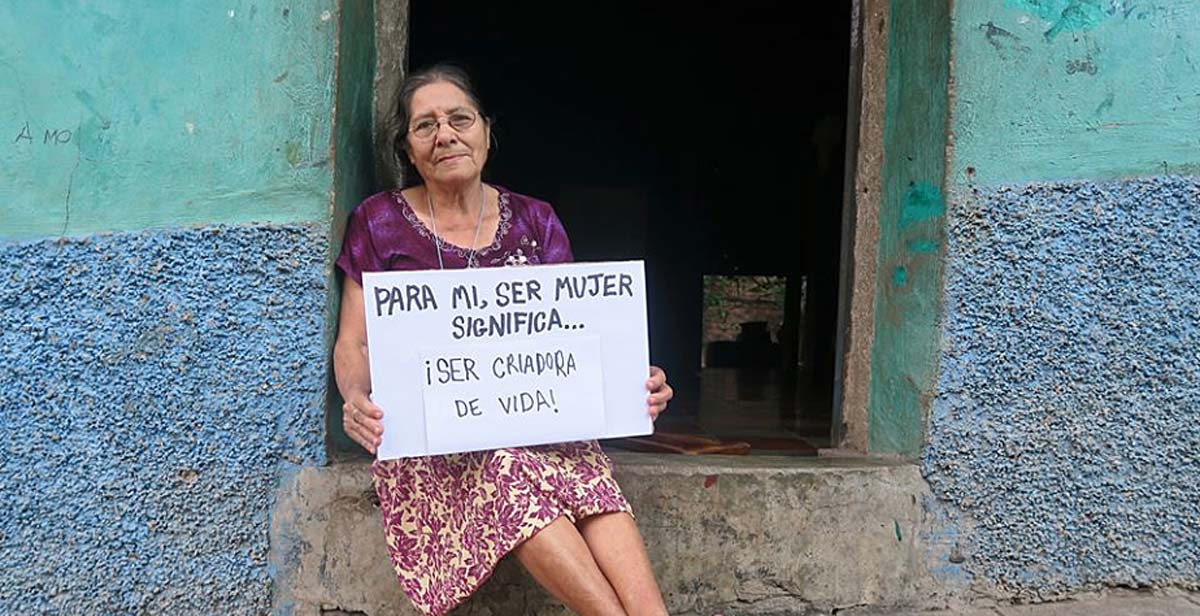

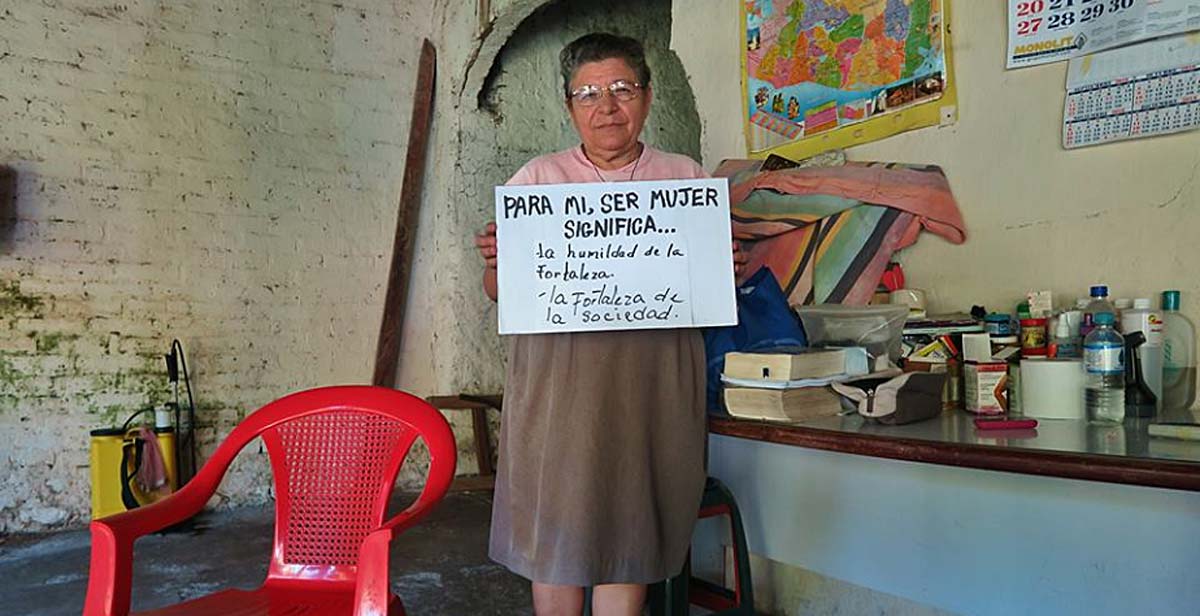

In anticipation of the International Day of the Elimination of Violence Against Women we wanted to hear what the women here in Arcatao had to say. We decided to go around the community asking ‘what does being a woman mean to you?’ and quickly we started accumulating a growing collection of photographs featuring local ladies starting a conversation about the importance, rights, and the capabilities of women. This conversation of empowerment was developing not just between the women photographed but amongst the whole community who came to visit the photography exhibition. Below are just some examples of the photos featured:

Grandmother: 'To me being a woman means being the creator of life!'

Shopkeeper: 'To me being a woman means living a life free from violence.'

Mother and daughter, 'To me being a woman means not being oppressed by anyone!'

Maria Chichilco, Guerrilla Leader during the civil war: 'To me being a woman means being the humility in strength, and the fortitude of society.'

Female construction worker: 'To me being a woman means having the capacity to do what one wants.'

Encouraging the women of Arcatao to send these messages of liberation to their community is one way of catalysing the long-term goal of gender equality, by emphasizing that women can and will work in typically male jobs like construction, that they refuse to be oppressed or mistreated by anyone and that they demand to be the leader of their own destinies. Another way is through continued education. Not only including issues of gender equality within the syllabus for all students but also the encouragement for female students to continue their studies. Often women are discouraged by their partners who want them to stay at home to look after the children, which in turn limits their financial freedom and their opportunities, increasing chances of patriarchal violence in the household. Breaking this cycle can be approached by small actions, such as men teaching their sons how to do housework and make tortillas.

As much as prevention is key, support for survivors of gender-based violence can also help reduce future incidents. By offering sufficient resources of psychological therapy, physical rehabilitation and legal help, as well as solidarity and support from the community, women and girls will feel safer to denounce any violation. They will feel confident that their words will be listened to, believed, and that they won’t be blamed in any way. They will feel secure because their perpetrator will be brought to justice. They will be able to start feeling happy and at peace once again because they will not suffer psychologically in silence, but instead receive professional help. When abusive men witness this change and see that their actions will not go without consequences the rate of violence against women will drop. I have hope that this progression will come in the close future with specialist governmental organisations like ISDEMU (Instituto Salvadoreño para el Desarrollo de la Mujer - Salvadorian Institute for the Development of Women) sending more resources to the rural areas, but the most powerful weapon to fight sexism is within each individual.

It was a workshop with Gabriela Miranda, a Mexican feminist academic, that taught us the single most helpful thing we volunteers can do is to learn. To learn from Maria Chichilco, a guerrilla leader during the civil war, that you mustn't let your gender extinguish the fire in your soul. To learn from Helia Rivera, head of the local women’s organisation, that you can come from a background of extreme poverty without education and end up getting paid to fight for equality. To learn from Ana Maria, our bio-construction guru, that females are just as capable as men at using a pick axe. To learn from the Salvadoran Representative for Progressio, Carmen Medina, that if we want to be able to help others we have to be able to look after ourselves. And to learn from all the citizens of Arcatao that you can fight through the darkest times of oppression and come out the other end carrying a better future for the next generation.

If there’s anything this community knows, it’s that a revolution for a better quality of life starts with the unity of the people.

Written by ICS volunteer Laura King