The climate, the noises, the smells, the bugs; these were the kind of things we thought would be a challenge before coming out here. Something I didn’t expect to be such a big adjustment was the food. From rice and beans (the bread and butter of Nicaragua), to the inevitable tortilla served with every meal or the tangy taste of the local cheese, Cuajada, all things culinary in Nicaragua have been a discovery in their own right.

We waved goodbye to consumerism in general as soon as we stepped off the bus that brought us to El Bram, and that’s been clear in terms of food (unless you count the high consumption of ‘choco-banano’ and ‘Quesi Trix’ bought by the Brit volunteers from the local shops). Firstly, nothing goes to waste. If you throw down mango peel, or leave some rice on your plate, rest assured it will be gobbled up by the nearest chicken, pig or dog guaranteed to be waiting in anticipation as you cook or eat, or your leftovers will go to make natural compost (abono). A few cheeky characters are known for eating more than their share; there is a cockerel notorious for pecking corn as it dries, and Rocky the dog has been caught stealing tortilla whilst they cook on the stove!

Not even tea bags go to waste here

Not even tea bags go to waste here

The other amazing thing here is that produce eaten has virtually 0 food miles; almost all food is sourced in the community based on what is in season, or can be bought an hour bus ride away in Condega, the nearest town. Tesco’s £1 avocados can never cut it once you’ve been able to pluck them (alongside mango and mamón) organically and for free from a tree three meters from your house.

Nevertheless, there are some cooking habits that are difficult to adapt to in El Bram, and it wasn’t long before we were cracking out the peanut butter supplies from our UK homes. On our first night in the community, our host mum Epifania (Epi) gave us deep fried plantain. It was delicious, and we thought it would be a one-off treat to welcome us into the community. How wrong we were. For the first two or so weeks, our stomachs were rinsed mercilessly by ‘aceite vegetal’ (vegetable oil). Fried rice and beans (gallo pinto), enchilada and banana were a daily occurrence. It took a while before we mustered the courage to ask for oil-free food. It was an even longer campaign to ask for less salt (especially on the tomatoes and cucumbers). In many ways, though, translation can only go so far. As Epi explained, she grew up seeing salt as 'opening flavor… the same goes for sugar', so getting some five a day in still comes at a salty price. We’re following this diet for only 10 weeks, but based on the common health complaints of the community (fatty liver, obesity and type two diabetes), in the long term, these cooking tendencies have devastating effects.

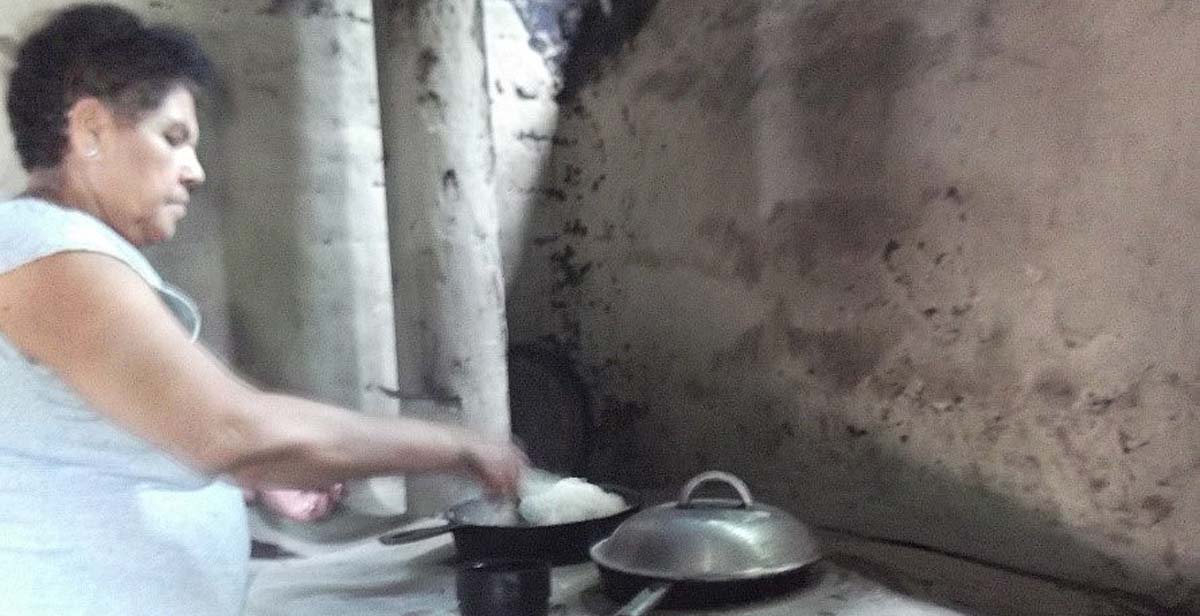

Epifania cooking at her wood burning stove: fun till you burn your fingers!

Epifania cooking at her wood burning stove: fun till you burn your fingers!

This is something we’ve been trying to turn around this cycle, even though it’s on a very local scale. For example, sourcing brown bread for the community shops, holding a health day and cooking healthy recipes with our host families. There’s been mixed success. I thought I’d given our host family salmonella after serving tomatoes stuffed with egg that was questionably cooked, and the reaction when our team leader Amanda gave her host mum Doña Lola olive oil was a funny one to watch too.

Buñuelos: a sweet maize treat, the Nicaraguan version of sticky toffee pudding. Consume with caution to avoid rapid weight gain!

Buñuelos: a sweet maize treat, the Nicaraguan version of sticky toffee pudding. Consume with caution to avoid rapid weight gain!

It seems we can both learn from our mutually distinct food cultures. I know for sure that I’ll be taking home some local coffee and chia seeds! Hopefully we’d have equally made a positive impact on the eating habits of the community by the end of the cycle, even if it’s only through loaves of brown bread.

Written by ICS volunteer Anna Klaptocz