Women in Latin America face an uphill battle to obtain even the most basic human rights. This struggle is augmented for Indigenous women, who embody the familiar double-edged sword of many conflicts in Latin America, which battle over the ownership of territory - both land and women’s bodies. As occupants of the bottom of social hierarchies in the region, being Indigenous and being a woman interact such that not only the fact of being female acts as a barrier to services, education and justice, but belonging to a marginalised ethnic group aggravates the hurdles through a network of detrimental social circumstances. Coupled to this, the high rates of violence against Indigenous women are barely criminalised.

In Guatemala, Maya Q’eqchi’ women recently took their testimonies to the Supreme Court as part of the Sepur Zarco case to demand justice for crimes committed during the internal armed conflict (1960-1996). These included sexual violence, sexual and domestic slavery, forced disappearances and murder, inflicted by six military detachments, which settled in the Sepur Zarco region for the purpose of exterminating local inhabitants. During Guatemala’s 36-year conflict, sexual violence was used in a widespread and systematic way as part of the counterinsurgency policy of the State, but no officers have ever faced charges of sexual violence. Women were subjected to inhumane conditions, repeatedly gang raped and forced to cook and clean for the soldiers.

On 27 February, after three decades of impunity, two former Guatemalan soldiers were found guilty of crimes against humanity. As the first time where a national court heard charges against sexual violence during war, this was ground breaking for several reasons. First, the historic verdict - albeit only for two of the perpetrators - has been crucial for the advancement of transitional justice in many Latin American countries by treating sexual and domestic slavery as a war crime. Second, the trial set a standard of proof based on the testimony of survivors from population segments that are typically silenced and/or ignored. Third, and importantly, this ruling offers some hope to change the mentality of defeat that women have developed in their struggle to access justice and end impunity.

It is critical to dismantle the culture of impunity surrounding sexual violence. Yet, while the pronouncement of “we believe you” after 30 years in the Sepur Zarco trial is to be commended, it also underscores much deeper issues that must be addressed systematically. The apparent ease with which violations are committed, especially against Indigenous and Afro-descendant women, is founded on deeper social and structural inequalities. To understand the real depth of the problem, the concept of “additive” or “multiplied disadvantage” can serve as a compass. We are embedded in a social embroidery composed of social roles and structures that interact in our personal reality. While not all people who identify with a social category - be it “women”, “Indigenous”, or “campesinas” - have the same experiences, the concept of additive disadvantage lies at the intersections between these identities and appropriately explains the ‘layered’ disadvantages experienced by those located at these junctions.

We see the tentacles of multiplied disadvantage in the nexus between ethnicity and gender. Acts of violence inflicted on Indigenous women follow on from such intersecting prejudices. Victoria Tubin Sotz, a Q’eqchi’ woman involved in mobilising various mechanisms to obtain justice for the Sepur Zarco women, articulated the importance of acknowledging the weight of racism when talking about violence against Indigenous women. She highlighted that not only are these acts anchored in a patriarchal scheme, but added to this is “that racism, that ambition to annihilate”: the historical contempt towards the Native Peoples. Mark Lattimer, Executive Director of Minority Rights Group International, voiced similar thoughts in the 2011 release of the annual State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples Report. “Women from minority and indigenous communities are deliberately targeted for rape and other forms of sexual violence, torture and killings because of their ethnic, religious or indigenous identity”, says Lattimer, referring to the multiple levels of violence due to ethnicity, class, and gender.

The biggest danger lies in the collective amnesia that has forgotten the value of these rural women and which silences acts of violence against them.

That said, violence against Indigenous women does not only manifest itself in particular instances of aggression. On a structural and institutional scale, additive disadvantage can problematize social inclusion and deepen the gaps of some development goals. Across Latin America, the estimated 50 million Indigenous peoples often occupy the lowest socio-economic spaces and live in remote areas, and are twice as likely to be poor compared to other Latin Americans. In Bolivia, where more than 60 percent of people identify themselves as Indigenous or Afro-descendants, Indigenous women face a higher risk of being excluded. There, an Indigenous rural woman is five times less likely to complete secondary school than a non-Indigenous urban man.

Indigenous women are female in a predominantly patriarchal society, from an ethnic minority in a society which admires “Western” values, and poor and rural in a society in which wealth is an important social marker. This is, in fact, a triple disadvantage.

In an attempt to escape the lack of economic and academic opportunities at home, coupled with the high risk of gender-based violence in rural settlements, Indigenous women often leave their ancestral territories for urban centres, where they face new struggles. While there they have greater access to education and clean water, the discrimination they face is great and the jobs they can obtain are menial.

In many Latin American cities, Indigenous women make up a large proportion of domestic servants with little labour rights protection. During a meeting I attended in La Esperanza, Honduras, organised by CICESCT (Comisión Interinstitucional contra la Explotación Sexual Comercial y la Trata de Personas) and Casa Alianza on the issue of women’s rights, the spokesman for CICESCT reported that, in their majority, domestic servants lack social insurance and are verbally - and in many cases, physically - assaulted. In fact, “mucho pegue y poca paga” (a lot of beating, a little pay) seems to be the ‘best’ expected outcome when leaving to Tegucigalpa and San Pedro to work in wealthy homes. Indigenous girls and women are forced to strip out of their traditional dress, have to change their idiomatic patterns, and are often referred to as ‘Maria’ as a blanket nickname, so entirely obliterating any remnant of ethnic identity and human value. But those who get paid are seen as the ‘lucky’ ones. Unfortunately, in many cases not being paid for 18-hour days is the fate of some of these women who get trapped into forced servitude.

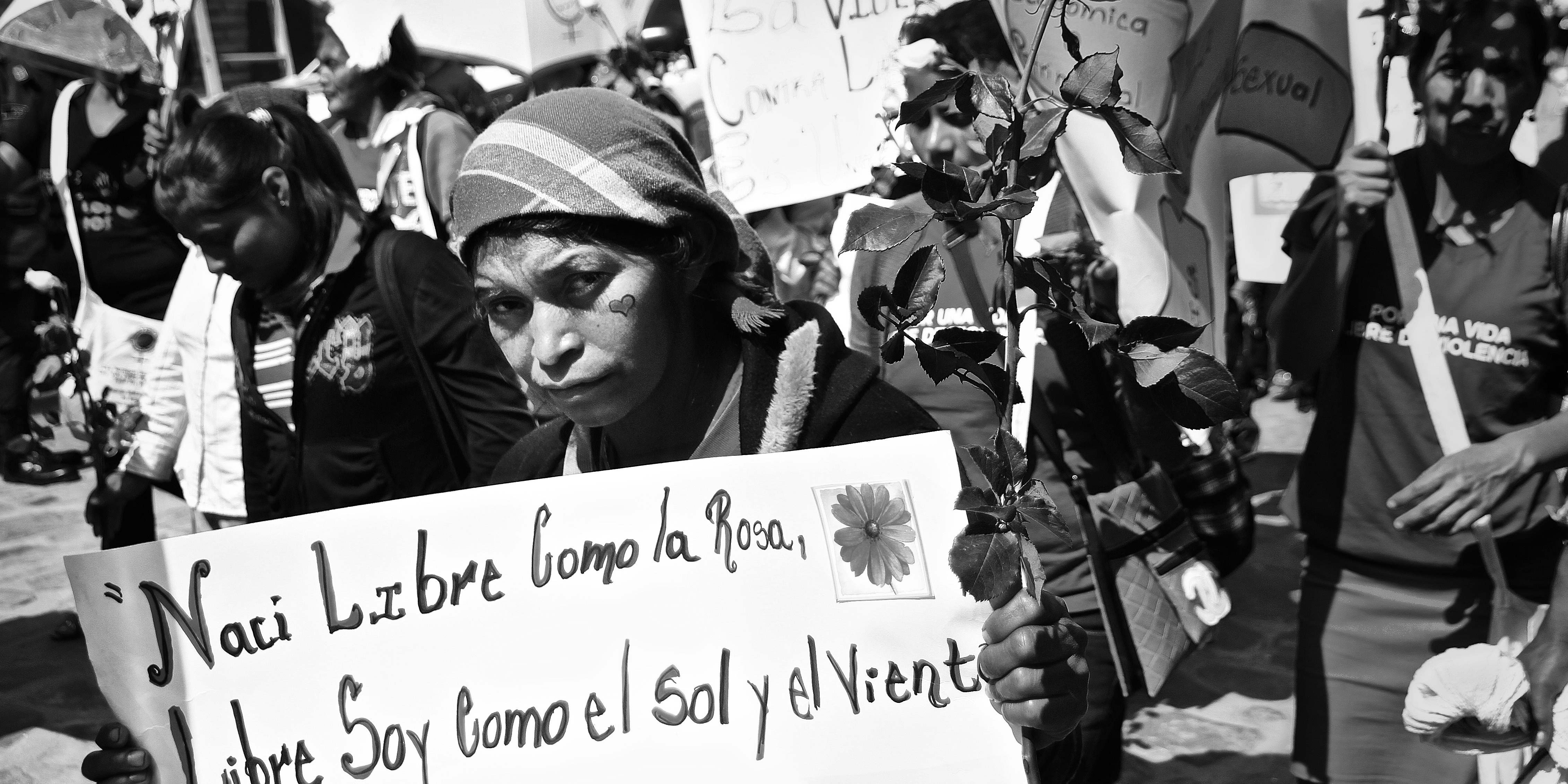

With these commingling layers of disadvantage, gender and ethnicity are as political an agenda as any other. Much has been achieved over the last decade in Latin America to tackle the epidemic of violence against women, with the uniting efforts of grassroots movements, local NGOs and international organisations. However, it is imperative to recognise the plurality of voices in the plight for ‘women’s rights’, and that violence against women often has a particular ethnic or racial dimension. Within these, there is further plurality: Indigenous women are not a homogeneous group, but have a wide variety of situations, needs and demands.

It is also crucial to acknowledge and protect the fundamental role of Indigenous women in the promotion and protection of human rights. Women in Latin America are struggling for their rights and for their participation in decision-making; communities are rising against projects that are framed as ‘development’ but in fact only signify their forced displacement and the undemocratic death of traditional livelihoods. Many Indigenous women are active human rights defenders of all individual and collective human rights of their peoples.

However, their efforts are still attacked. In a bleak prelude to International Women’s Day, the Honduran indigenous and environmental rights campaigner Berta Cáceres was murdered in her home last Thursday, 3 March. As a Lenca woman, she was profoundly committed to protecting the rights of Lenca communities and their natural resources through the grassroots mobilisation of workers, of women, of Indigenous people and campesinos, reason for which set up the Council of Indigenous Peoples of Honduras (COPINH). During my placement, I had the opportunity to work with her colleagues through weekly radio shows on the Indigenous community radio platform of La Voz Morazánica. Upon winning the Goldman Environmental Award in 2015, Cáceres vowed to continue standing up for the rights of nature, women and Indigenous communities, and dedicated the award “to all the rebels out there”.

It is this spirit of rebellion which characterises those fighting for the empowerment of women, for the empowerment of Indigenous communities, and more broadly, for justice. Yet those who lead these movements are castigated systematically. Berta Cáceres is another victim of the paradox that plagues the voices of the unheard: speaking up for Life and earning a death sentence. Ironically, in Honduras it is those who have stood up about injustices such as the shocking femicide rate - which increased by 260% in the last decade and contributed to a woman being killed every 16 hours in 2015 - and the discouraging rate of impunity - over 96% - which have been targeted.

With this lack of accountability, the social acceptance of violence, specifically against women, has become normalised. Women in Honduras have been fighting against impunity through collectives such as Foro de Mujeres por la Vida, Las Hormigas and Visitación Padilla, members of which are commonly known as the “Chonas” (women of feminist ideals). The Coordinator of the latter, Gladys Lanza, was convicted of defamation last year for defending a woman who accused a Honduran government official of sexual harassment. No government can hope to improve in matters of human rights when it uses the power of its institutions to persecute defenders of these rights. In fact, the judicial system is one of the biggest obstacles to implementing international tools that would protect women, such as the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, which Honduras has not ratified. The state and its institutions, therefore, are highly implicated.

Parallel to the activism for women’s rights, the increasing visibility of Indigenous peoples’ organisations has been important for governments and international agencies to pay more attention to their demands. Yet, the bottom line is Indigenous women, especially, remain invisible within Latin American society.

Analysing the situation of Indigenous women requires intersectionality between gender and Indigenous perspectives, which involves considering the concept of well-being, the situation of indigenous women within communities, their priorities and needs, including access to and control of the territories. Even though laws may convict women, and society relegates Indigenous women to a peripheral footnote in legislature and its practice, legitimacy envelops their efforts at visibility and justice, their courage, their resistance.

The structural barriers that prevent women and Indigenous peoples from accessing any degree of social mobility can only denudate if the courageous women who have exhaustingly sought redress are seen as valuable political actors. And it is time Latin America faced the threefold challenge with the endurance of its most vulnerable inhabitants.

Written by ICS Alumni Maria Faciolince (October - December 2015 cycle)